This post is a transcription of Survival Treatise – Exams, which can be found in its original format in the pdf linked below. Some of the fonts utilised in the original may not be everyone’s cup of tea which is why I have decided to transcribe it below.

Survival Treatise – Exams © 2024 by Chiara Selene Ferrari Braun is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

ESSAY

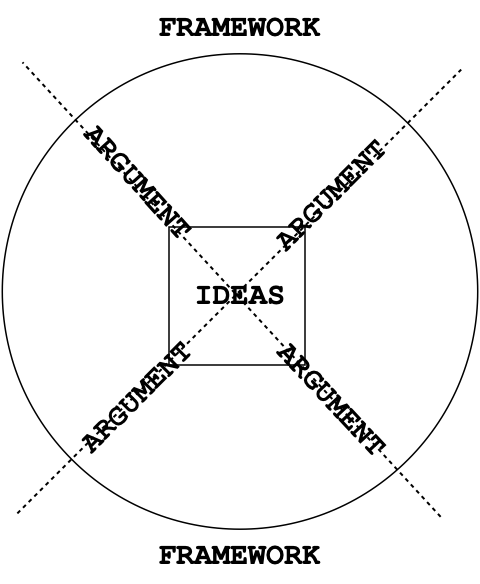

Framework

The beginning of an argumentative piece, should always be rooted in the response to a pre-existing approach. It will be rare to find yourself, as being the first pondering questions about a given subject.

Outlining the scholars and the ideas you wish to engage, side with or challenge, structures your work giving it a beginning and an ending.

Much like lego or geometry, the previous ideas should be utilised as blocks to build your own through support or opposition.

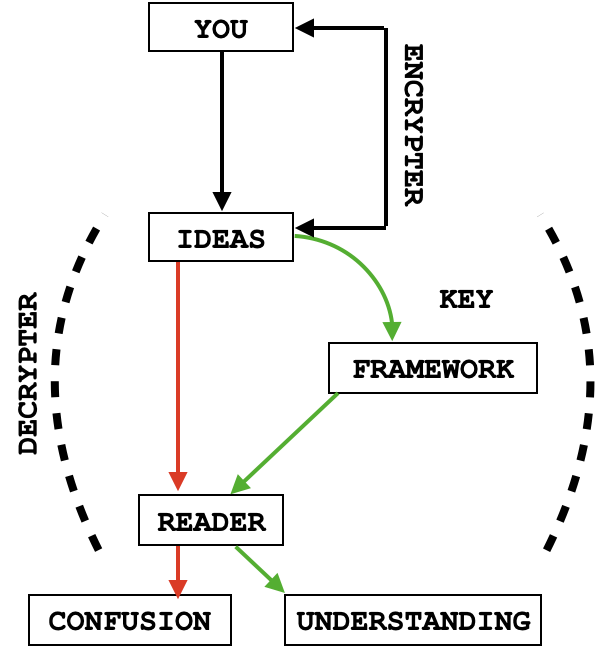

In spite of how brilliant your ideas might be, your readers are not in your head. You have to give them keys to decipher the inscription, in this case, the framework.

The framework should also include both the timeframe you will move in and the definition of key terms. These definitions are essential as they will help narrow your scope and it will limit the grounds on which you can be theoretically accountable.

Therefore the framework is composed of:

- Thesis

- Historiography

- Timeframe

- Definitions

Its bounds are presented in the form of the introduction and it is a constant companion.

At any given point at the top of your notes/exam, a post-it note or a piece of paper should house a ‘machete’ showing:

Thesis……………………………………………………………………

Historiography………………………………………………………

Timeframe…………………………………………………………….

Definitions…………………………………………………………….

Introduction

This is your war declaration. It is the statement that will define everything that follows. Failure to properly execute it, will lead to an uphill battle with an examiner that is probably overworked after reading 1204 copies of people that believe they are the next Baxandall.

In the introduction you will hook the reader, the same way the Philistines got Samson but less explicit. Usually done with a clever quote or a nice opening sentence. Do not go dreamy style as your relationship with your readers is akin to Tolkien’s and his editors (you are not Tolkien in this scenario) if you use metaphors or overgeneralise you will be hunted down. Anything you write will be used against you when marking.

Does this give you trust issues? Yes. But it is better to have trust issues and good marks than overconfidence and a 3rd. Besides, if it does not destroy your mental health it is not a University of Cambridge certification.

[The author understands that the abuse of references towards the Oxbridge experience might alienate the audience, however catharsis is as important to the writing of this work as is its utility]

Once the hook is complete we are moving onto the question. This allows you to establish your framework.

As we previously established answer these questions:

- Why is this a relevant question?

- Does this happen in a specific timeframe?

- Who has asked or answered this question before?

- What is your position? AKA your opinion/argument

- Opportunity to present the outline.

Cheat code is on there as well:

Thesis……………………………………………………………………

Historiography……………………………………………………….

Timeframe……………………………………………………………..

Definitions……………………………………………………………..

Easy way of setting it up is the very boring phrase:

“In this essay we will…”

“This essay will…”

“To this end, this essay will…”

Straightforward pipeline of an outline: say exactly what you are doing and how.

Is it terrible writing form? Yes. Will it kill you to do it 17 times in the spawn of 5 exams? No. Will it be annoying and you will not want to do it after the first exam? Yes. Reason why this whole thing exists, get on with it, no excuses, less drawn out annoyance, better marks.

Body of the work

The objective of the body of the work [sounding like Zaugg, right about now] is to build up your case with evidence and a structurally sound progressive/logical succession of ideas that flow into each other like a river.

Each idea is build up through an argument that ties in with the larger thesis.

Structure of an argument

Key idea (your own)

- Framework

- Who has already gone in this direction or who has gone in the opposite direction?

- Example that illustrates their points, preferably visual (we are visual animals).

- Opposition/Challenge/Endorsement

- How does it apply to my subject/question?

- Hook/connection to the next paragraph either taking on a different point or further exemplifying your idea.

Build on, and build on, ideas should be a one-line statement, quick, sweet, and non-indulgent in over-explanation. Do yourself a favour and argue with your examples rather than grasp at ontological ideas that will lead down the rabbit hole of your randomised synapses.

Conclusion

In a previous edition, the 1st one, the conclusion had been forgotten. Therefore allow me to provide you with the most important piece of advice regarding conclusions.

Conclusions are not easy but they are not the final boss, that’s you and your mentality of ‘I can play the examiner’ and ‘I’m oh so clever’. You are putting everything you have exposed in the paragraphs above into a neat little package that essentially says, it proves or disproves my thesis. Other matters can be addressed in the conclusion, for example, linking or exalting the relevance of the chosen cases in view of your thesis. You are concluding, thus, you should not introduce anything new unless you want to invite to further discussion or inform the marker that you are aware that the field is far larger than what you can explore in this work. I would not recommend to do this in the exam setting as it might backfire.

VISUAL ANALYSIS

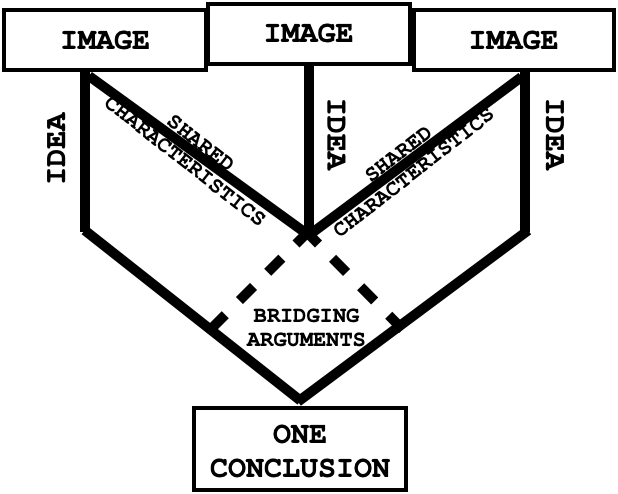

As Lazarus, we rise from the image.

As long as you know what to say about the images and what links them together you can make a braid with your arguments, the complexity of which depends on how many arguments you got.

END NOTES

This work was originally written during an exam period, it was meant to be a personal guide that would keep me, the author, on track and avoid the general pitfalls that had previously been remarked upon by my supervisors. It is tailored to essay writing in exam setting, which emphasises time management and repetitive structures as well as lacking any in depth information on citation or footnotes as these are not expected to be done beyond a rudimentary inclusion in the writing itself (usually: author, year, and maybe publication).

I found myself sharing this work around to other fellow students, whom I suspect took much more enjoyment in its quips than any useful tips from its pages. I find it quite funny as well and I have decided to put it out there so it may be of service whether for laughs or proper academic help.

[This author is not responsible of the bad or good results you might garner from following these steps, though I would appreciate the good fame]

To my supervisors who had to bear with my prose for three years, especially Dr. Ralph St. Clair Wade who had to get through my thick skull that ideas are great but doing the exercise in its terms is what will pay-off.

In the end it did!

Survival Treatise – Exams by Chiara Selene Ferrari Braun is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Leave a Reply